Note: This is a translation of my Japanese article “計算機科学から見たディープラーニング” in a Japanese technical magazine “n-monthly LambdaNote Vol.1 No.2”.

It has been a few years since people began to say that “deep learning is great.” Some readers may already be immersed in deep learning. Given the rise of deep learning, it is also said that it is now in the midst of the third AI boom, so now many people are involved in AI-related projects even though he/she is not familiar with deep learning.

The boom will fade out someday. However, the deep learning behind the current AI boom has already been implemented in many applications and has achieved remarkable results in numerous application areas. In image recognition, in particular, it has become beyond human accuracy. Therefore, even if the AI boom goes away, deep learning technology itself will be incorporated into many of the software in the world, and it will continue to be used as one of the techniques familiar to our lives.

Because it becomes part of our lives, I think that software engineers, such as programmers, need to properly understand what kind of technology deep learning is in the first place. However, at this point, the theoretical elucidation of what deep learning is is not entirely done. Many feel that they can only understand vaguely what deep learning is.

So, in this article, I will re-evaluate what deep learning is from the perspective of computer science and a little bit of software engineering. Specifically, I would like to introduce an attempt to reconsider deep learning as a new programming paradigm.

Attempts to recapture deep learning from this point of view are not unique to me, but various people who are involved in deep learning express similar ideas in diverse expressions at the same time. Especially overseas, a blog1 by Andrej Karpathy, Director of AI department of Tesla, derived a keyword Software 2.0 and had a great response, and now many are using this word to express the idea.

I think that some of the content described in Karpathy’s blog can be highly supported, but that the optimistic stance remains somewhat skeptical. Therefore, in this article, I will actively promote deep learning as a new programming paradigm referring to Karpathy’s point of view, and try to organize and consider what kind of tasks are waiting in the future.

Note that this article does not touch on the structure of deep learning itself. There are many introductory books and articles in the world, so please refer to them.

What Constitutes Software Development

Before going into the main topic of deep learning, let’s first consider what is software development without deep learning.

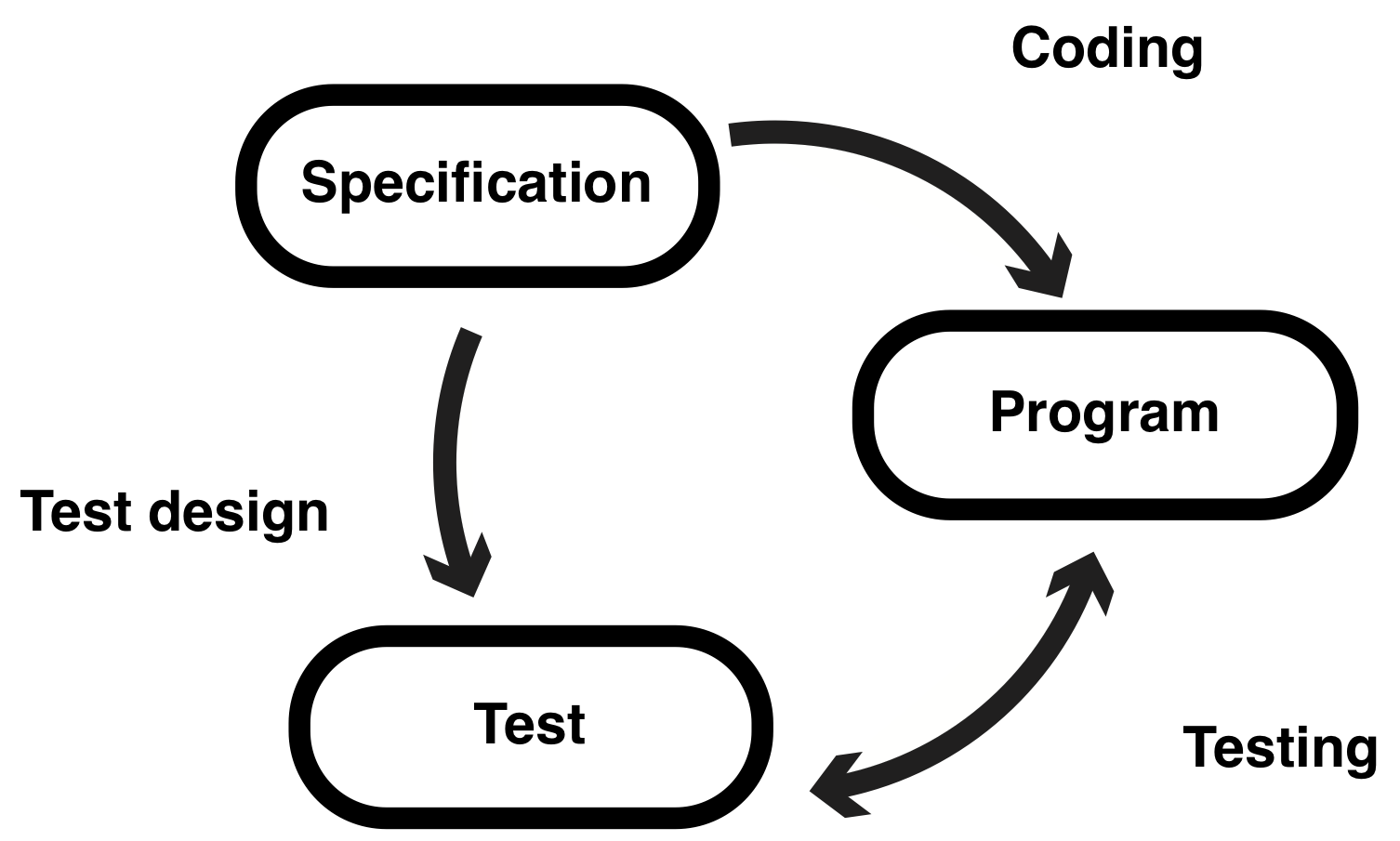

In general, software development is considered to consist of three parts: specifications, programs, and tests (the figure below). Although I describe the design, coding, and testing as the arrows connecting the three elements in the diagram, these terms have no profound meaning here.

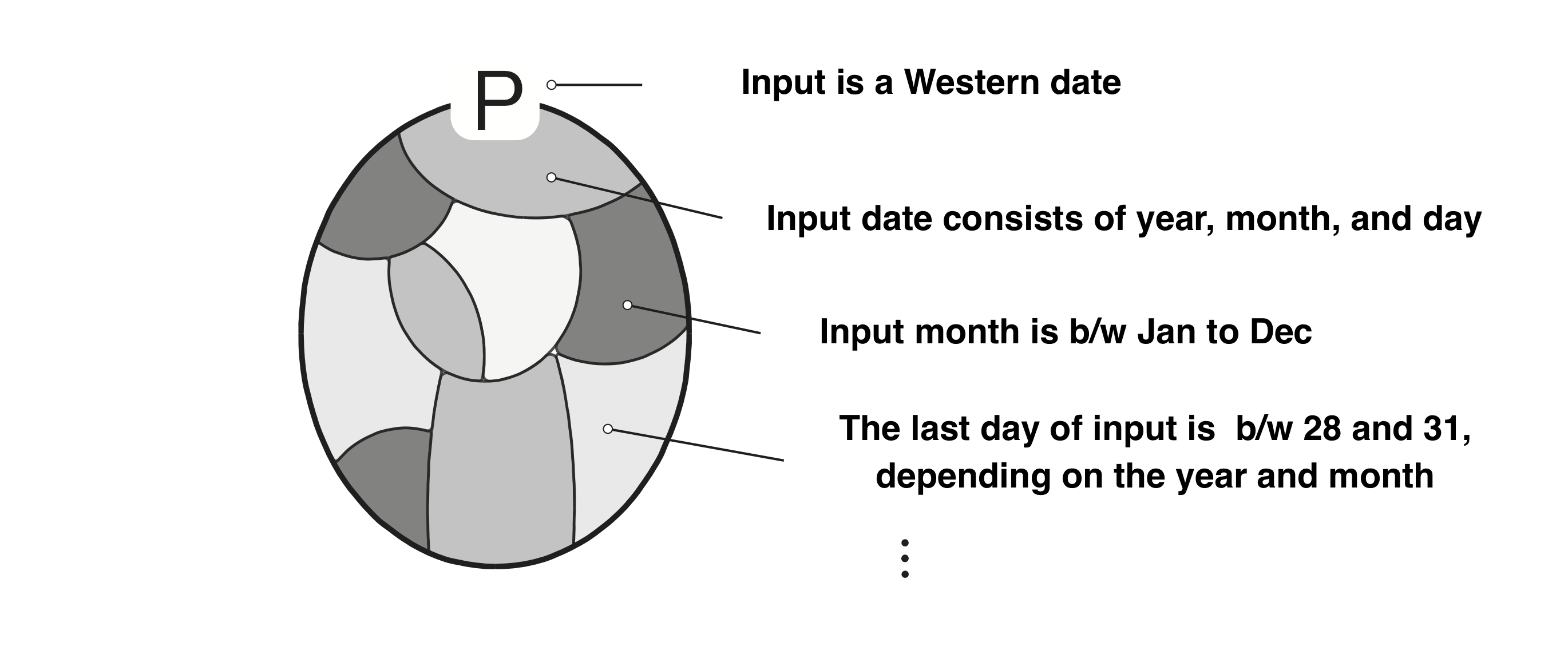

Let’s think about the relationship between specification, program, and test a little more concretely using simple examples. Suppose that you want to create a program that takes a date in AD and returns the day of the week. The input and output of this program could be described as:

- The input is a valid Western date.

- The output is the day of the week corresponding to the date entered.

When making a program, whether to document such things depends on the development site. But, at least, you should start development with the content that can be expressed in such assertions in mind. And at this time, it is to be considered that the pair of “input is a valid Western date” and “the output is a day of the week corresponding to the input date” is the specification of this program. I do not think there is any objection about how we can say it like this.

The conditions for a program to work correctly, such as the former statement, are called preconditions in computer science. And the latter condition that the program realizes until it works normally is called postcondition. The two are always used in a pair, as the precondition changes and the postcondition also changes.

The “precondition”, “postcondition”, and “program” triplets are denoted as {P} c {Q} hereafter. Preconditions apply to P, programs apply to c, and postconditions apply to Q 2.

This notation is called Hoare triple. If you write the previous example in Hoare triple, it becomes the following expression.

{Input is a valid Western date} Calculation of the day of the week {Output is the day of the input date}

The above is a valid expression as a Hoare triple.

From a Hoare triple {P} c {Q} we think that c always ends up in Q when it is executed under the condition that satisfies P 3. And we assume that this holds in all states that satisfy P. In this example, “the day of the week calculation program will always output the day of the week if a valid date is entered”.

A program c is what is filled in between the precondition P and the postcondition Q in a Hoare triple, and the task to fill in between is programming. Without a program, preconditions and postconditions, i.e., specifications, are just a pie in the sky. On the other hand, without a specification, we cannot know what the program does. In that sense, of the three elements that appear in the diagram above, we can say that the specification and the program are inextricably linked.

So what is the “test” in the diagram? A test (here we consider a so-called functional test) usually consists of pairs (i, o) of the input i and the expected output o. And these are examples of precondition P and postcondition Q. Note that it is unknown in testing that the expected output is the actual output of the program, so o is not just a mere output, but is called an oracle (or a test oracle).

In the previous example, let’s create an expression with i = April 26, 2019 and o = Friday.

{April 26, 2019 is a valid date of the year} day of the week calculation {Friday is the day of April 26, 2019}

April 26, 2019 is certainly Friday, so if the day calculation program works correctly, this formula will be satisfied.

The important thing here is not only whether a particular test is satisfied, but the more you collect the valid tests (i, o) anyway, the closer the set gets to a pair consisting of P and Q. To put it a little more accurately, the following two are both expected.

- The set of all the correct test inputs

ican be identified with the state space indicated byP. - All

(i, o)sets satisfyQ.

In practice, it is almost impossible to collect all the correct test input i. So, in practice, we will sample a small fraction in the space that meets the specification and design tests with only a few elements that represent the space of (i, o).

It is not about test design that you want to focus on here. The point is that if you collect tests, it will get closer to the specifications. If we push this recognition forward, it will lead to a notion of “substituting specifications by testing.” In the following, we will refer to this kind of view and call it test as a specification.

Note:

In recent years, especially in the context of agile development, development methods have been developed that emphasize testing rather than writing specifications strictly. The background behind this method is similar to “test as a specification.” In fact, the idea of test-first is to “write a program that meets the test” instead of “write a program that meets the specification,” which we can view as an example of “test as a specification.”

So What is Deep Learning?

In the previous section, I did not assume deep learning in particular but tried to think about general software development through Hoare triple. Now let’s think about deep learning. As an example of that, let’s start with an image recognition program. For example, if you have to create “a program to determine cat images” by your own hands, how can you code it?

It should be quite challenging to characterize the parts of the image that correspond to the ears, nose, and tail, and to write down a code to determine if there is a cat or not based on their positional relationship. Even more, the color of the body hair and the shape of the tail are various, so the level of difficulty will be even higher. Unlike the example of calculating the day of the week, which we consider as an example in the previous section, programs that recognize cat images are unlikely to be easy for humans to write down programs that can be interpreted by computers.

However, with deep learning, you can easily obtain a “program for determining cat images.”

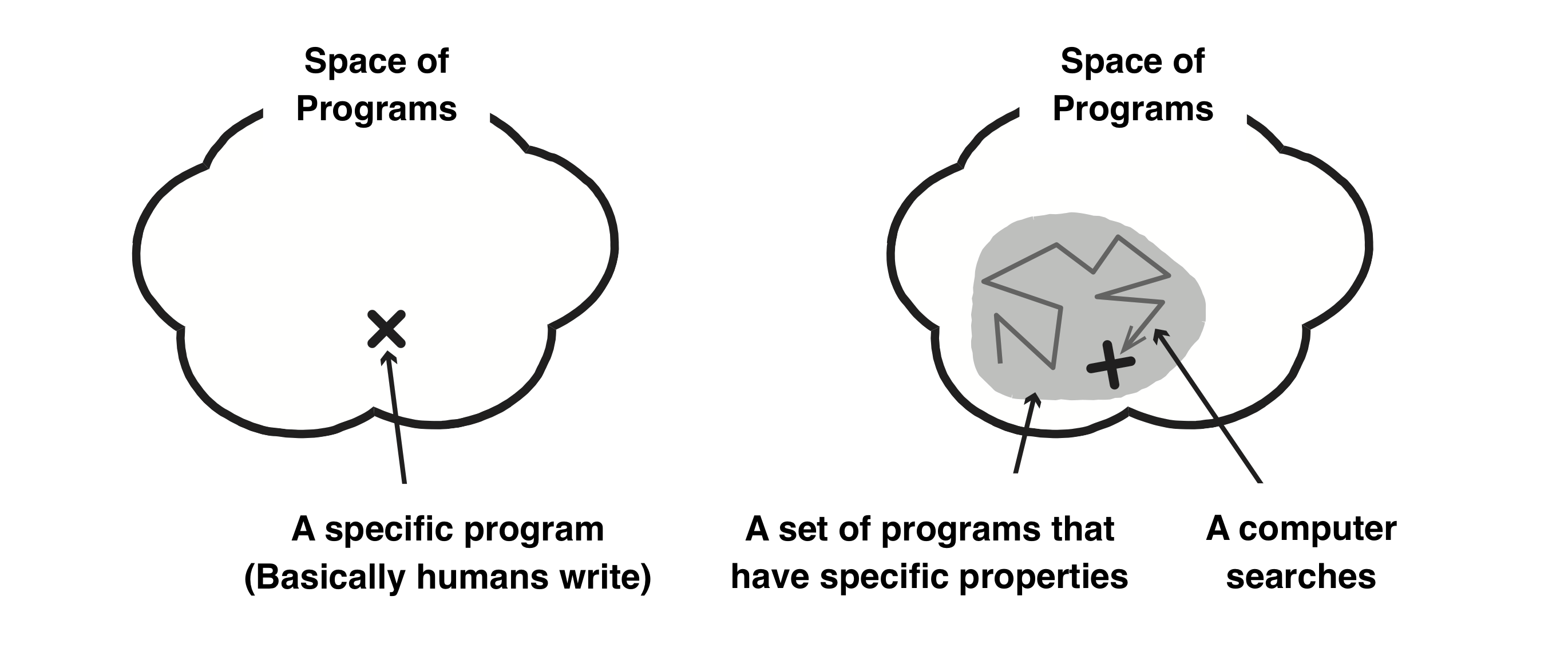

To get such a program in deep learning, we first design a neural network. Specifically, after defining a simple specification such as “determining whether there is a cat in the image,”we write code that will be a rough skeleton. This code defines a set of programs that have a particular property, or a space in which programs gather. Then, a computer searches for a program that is most suitable to satisfy the specifications in this space by using computing resources (right of the figure below). This method is in contrast to traditional software development (left of figure below) where humans have described “a specific program.”

Note:

Andrej Karpathy, Head of AI at Tesla, derived a term Software 2.0, which represents software development in a way in the diagram above on his blog. In fact, the figure above is based on his blog, which shows the difference between traditional software development and Software 2.0.

Deep Learning Programming by Test

To summarize the above, there are the following differences between conventional software development and deep learning.

- In conventional software development, humans write a program that meets the specifications.

- In deep learning, humans determine a space where candidate programs gather, and in this space, a computer searches for the optimal program that satisfies the target specification,

In deep learning, a computer searches for a program that meets the specifications. That means that the machine needs to be able to interpret the specs. However, specifications such as “the image with a cat” are not in a form that can be understood by a computer as it is.

So, what to do in deep learning is giving a set of tests as a specification. In the deep learning and machine learning world, the collection of tests given at this time is called “teacher data” or “training data.” When you want to say a specification that “there is a cat in the image,” a large amount of cat images tagged with “cat” is given to the computer, and the computer searches for a program that determines each image as a “cat.”

This way is very different from conventional software development, in which programmers write a specific program that meets the specifications. Instead, this is a more ultimate form of the “test as a specification” mentioned at the end of the previous section. In other words, deep learning is programming by tests.

In more general terms, we can say it is programming by data. In traditional software development, we use a human-written code to determine programs. In deep learning, a code only defines the outline of the program. The final program is determined by a set of tests given as a specification, that is, a set of data.

So, the most important thing that humans should do in deep learning is to assemble the data. If you have a lot of bad stuff in your data, you can easily get a lousy program.

The amount of data is also essential. Testing is also necessary for traditional software development, and it is also required to have the data assembled. However, such tests do not necessarily require massive amounts of data. Usually, the programmers should have a simple specification in their mind, and there are undocumented common sense and business knowledge. Even in a test-first manner, we implicitly assume programmers can supplement specifications through such things, so a vast amount of data is not always necessary. But in deep learning, computers only understand tests. There is no common sense or business knowledge to be premised, and a large amount of data is required because the specifications must be estimated only from the set of inputs and expected outputs. Of course, as with typical test design, such data should be fully and evenly.

On the other hand, the amount of code you have to write is much less than with traditional programming. The design of neural networks requires coding, but this code only defines the space in which programs of particular properties gather, so it can be widely applied to similar tasks and is therefore highly versatile. In other words, it is useful for broader tasks than conventional programs. Thus, coding in deep learning is less prioritized in the overall process than coding in traditional software development (which of course does not mean that coding is not important).

Deep Learning is Inductive Programming

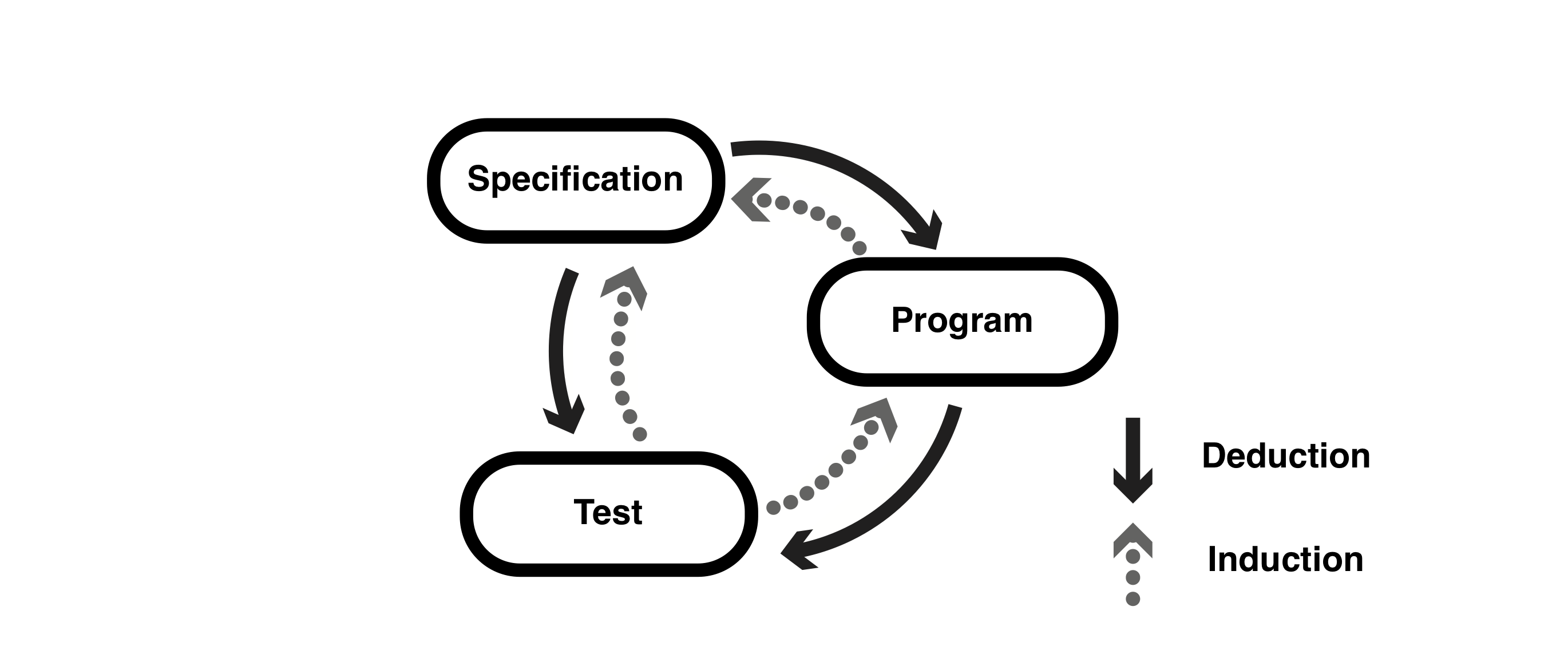

Here, I will change the figure shown at the beginning a little.

The figure above has the same composition as the first figure but adds the reverse operation to the arrows connecting the elements. The solid arrows in the figure above are derived from top to bottom and are called deduction. This corresponds to the operation of inferring more detailed or individual events from general rules along with the flow of A implies B in logic.

Deep learning, on the other hand, obtains a program from tests. From the tests that are specific events, we get more general rules as a program. Getting general rules from a set of individual events is called inductive in logic, so deep learning can also be called an inductive programming.

Note:

In fact, technologies called “inductive programming” or “programming by example” has existed before deep learning, and has been extensively studied primarily in the second AI boom 30 years ago. However, they used logic-based inductive reasoning, and most techniques used to estimate program code. Deep learning, on the other hand, is statistics-based and does not estimate code. Instead, they do program by auto-tuning the parameters of large mathematical functions with hundreds of thousands of arguments. So it can be said that it has completely different characteristics from inductive programming at the time.

Deep Learning Challenges as a New Programming Paradigm

Did you realize that deep learning has completely different characteristics from traditional software development, and programming methods are entirely different? Deep learning has expanded our programming methods greatly. With deep learning, you can even create programs that were previously unrealizable if you set an appropriate search space, and that far exceeds human capabilities. In fact, the accuracy of image recognition exceeds that of humans in 2015 4. Also, in 2016, AlphaGo beat Go’s world-class top player. These are all outcomes that could not have been achieved without deep learning.

In the first place, many programmers will flinch if they are said to create a program that determines a cat image with their own hands. However, with deep learning, it is quite elementary to develop a program that automatically acquires what a cat’s characteristics are, and determines whether it is a cat or not based on correlations between the features and the cat. This means that programs that programmers could not code can now be programmed using deep learning.

Thus, while deep learning allows for programming that exceeds human processing power, its coding is too foreign compared to traditional software development. Using Hoare triple {P} c {Q} described in the previous section, conventionally, coding is to define one c that satisfies {P} c {Q}. In contrast, in deep learning, coding is to define a set of cs that satisfy the specification.

What I am interested in here is whether we can discuss deep learning along with the Hoare triple like traditional software development. And I think there are three kinds of problems in deep learning, divided into precondition P, postcondition Q, and program c in Hoare triple {P} c {Q}. Let’s sort out what’s going on.

Problem with Precondition P: It is Extensional

In conventional software development, it was common to capture specifications in an intensional manner. Here, the term “intension” is a way of capturing a set like “an integer from 1 to 5” or “{x | x is an integer from 1 to 5}”, using properties common to all elements. In the day-of-the-week calculation example, I declared that the condition “the input is a valid Western date” and that everything that satisfies the condition meets the specification.

On the other hand, specifications can also be extensionally so that individually the elements can be listed that gives a set like {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}.

In the example of the day-of-the-week calculation, it is possible to list up concrete examples one by one and declare specifications as the extension like “January 1, 1990, January 2, 1990, January 3, 1990 …”.

In the sense of many people, an intensional expression will work more intuitively to the specification. Even if you develop an image recognition program for cats in deep learning, you may first consider the specifications in an intensional manner, such as “If a cat’s image is input …”. In that case, you have to translate it into an extensional specification by collecting concrete cat images.

In this way, such extensional specifications have two problems that come to mind:

- Extensional specifications are difficult to ensure completeness and sufficiency: In the case of cat image recognition, it is necessary to collect the images of cats of various breeds at all angles, A considerable number is required. Also, you cannot know well how many pieces about how many kinds are sufficient.

- There is a gap between the intensional specification based on human intuition and the extensional specification that you have to give actually: To confirm each image of cat’s as “it is certainly a cat’s image” is easy, but it is difficult to determine whether the entire set of prepared images matches the originally intended “image of a cat” specification.

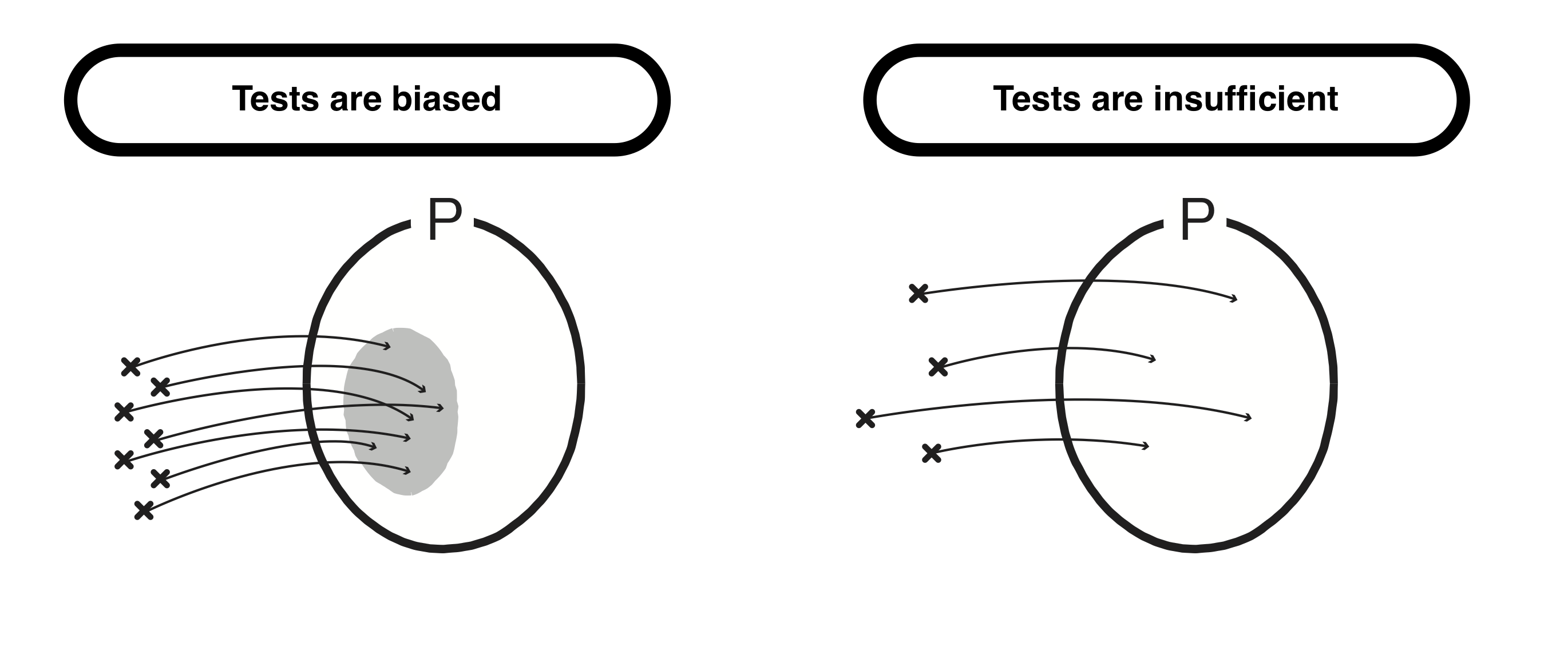

That is the story; with an extensional specification, it is easy to confirm that each specific instance always belongs to the area indicated by the precondition P. On the other hand, it is not easy to check if the set consisting of the whole example covers the area of P. It is not easy to break the possibility that there are biased areas, that all areas of P are not covered, nor that the number is insufficient and there are big interspaces (the figure below).

If we can make sure that the area of P is adequately filled, there is no hardship, but of course, it is not easy to make sure. Of course, if it is possible to state the area of the “cat images” explicitly, the program that recognizes the cat image at that point is completed by encoding the domain directly in a form that the machine can understand. Because it is not easy to do that, we are programming using deep learning, which provides a specification in an extensional manner.

In software development based on intensional specification, we fill in P not with points but with faces (the figure below). Therefore, ensuring the sufficiency for P is not so difficult. Of course, there is always the possibility of a specification leak, but it is less likely to be a problem than filling in the area with points, and it is relatively easy to check if there is a problem.

In deep learning projects, some problems are actually caused by the fact that this specification is extensive.

First, let me introduce one case that happened close to me as an example of deviation in specifications. In a particular project, they decided to add face recognition feature to cameras installed in some places in Tokyo, and developed a program for that using deep learning. At the time of development, it worked without any problems, but when they installed a camera with this function, the recognition rate was abysmal, and it did not work properly. When they examined what happened and found out the cause was that they used open data provided by a research institute abroad for training face images. Because it included faces of all races evenly, the recognition rate dropped sharply at the place where only all people appeared were Japanese. Another problem was the development team consists of non-Japanese mainly, and so they failed to discover the problem earlier.

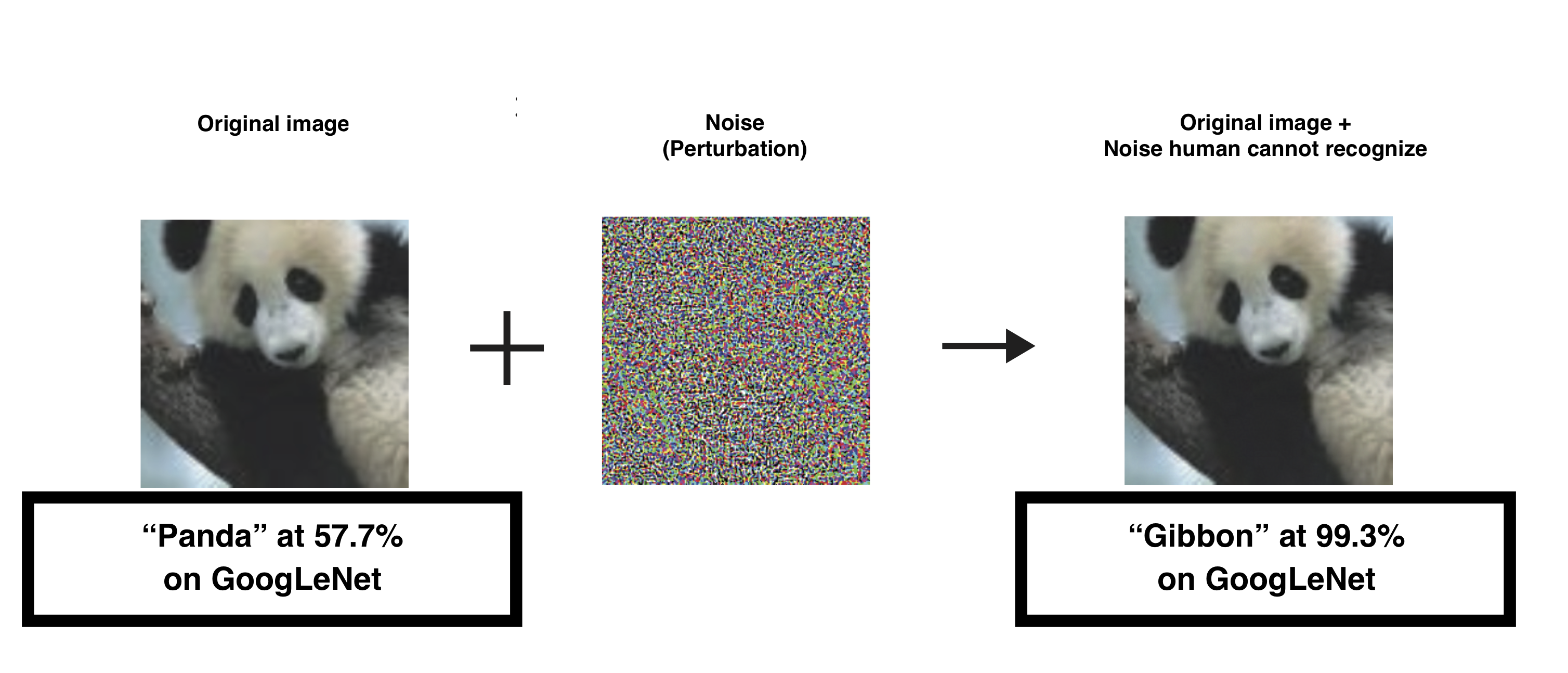

The existence of adversarial samples is known as an example of the problems that arise from not being easy to fill the gaps in deep learning. For example, for an image recognition program using deep learning, it is possible to cause the program to make a misjudgment by presenting an image carrying minute noise that is extremely difficult for humans to recognize (the figure below, quoted from a paper5). The adversarial sample is an inherently inevitable problem for deep learning due to the presence of recognition errors that can not be eliminated in deep learning.

Problems with Postcondition Q: It is Statistical

As mentioned above, in the background about the problem of preconditions in deep learning, the way of thinking of specifications could be very different from conventional software development. So what kind of deep learning matters for postconditions?

Conventionally, Q was a condition that holds for all inputs for which precondition P holds. Therefore, in traditional software development, programs are expected to be deterministic, that is, ideally, they work correctly on all inputs. If at least one example behaves differently than expected, it is surely a bug, and the program is considered to have something wrong. In the case of the day of the week calculation program, if “Sunday” is output for the input “May 2, 2019”, which is actually Thursday, we can determine that this program is wrong.

On the other hand, Q in deep learning is expected to be satisfied whenever possible. Due to the nature of current machine learning, it is not possible to create a program that answers on all tests (training data) correctly. In most cases, you can only create a program that makes a few mistakes. Therefore, a postcondition Q in deep learning is to be defined and interpreted statistically only.

For example, even when you enter a cat image into a program that recognizes cats using deep learning, and it determines “it’s not a cat,” we cannot judge that the program is wrong. Who knows, a program that answers correctly to 80 out of 100 will probably be judged as “correct.” Furthermore, we may have to judge another program that could only answer 79 pieces correctly as “wrong,” while the program that gave 80 pieces correct answers was correct. In the first place, a program that offers a correct answer rate of 80% at the time of development does not necessarily guarantee the accuracy of 80% at the time of operation. There is no guarantee that the distribution of test data used during development will match the distribution of input data during operation (remember the case of developing a face recognition camera mentioned above).

In other words, postconditions become an issue in deep learning because it is statistical. It may not be easy to divert programming and testing techniques built on the logic used in conventional software development into deep learning, which is a highly statistical technology.

Also, we do not usually use programs created by deep learning alone. In practice, it will most likely become a module in some system. At this time, how should we guarantee the correctness of the entire system? In other words, how do you handle system testing? In such systems, specifications P and Q for a deep learning module become an interface to other traditional software modules. We need to bridge the gap between statistical Q and the part that can be interpreted by conventional logic and programming languages.

Also, tests for deep learning modules built into a system may not pass individually. If we consider such cases in system testing, we may have to statistically evaluate how well it worked for the entire set of test cases.

Research papers have already been published at international conferences on testing and verification of systems using deep learning for several years. For example, several methods called “neuron coverage” have been proposed to evaluate neural network coverage based on the same concept as conventional code coverage6. On the other hand, a controversial paper has been published that question the effectiveness of these methods7. The paper describes experimental results showing the detection probability of the adversarial sample does not change even if you increase the neuron coverage and add tests based on the metrics. The author mentions that “the coverage is powerless for adversarial samples, as the adversarial samples are pervasively distributed in the more finely divided space than what such coverages assume.” After all, since there are only a few years of history, we cannot say that there are no enough methods that can practically be used for testing and verification of deep learning systems.

Problem with Program c: Illegible

As mentioned earlier, programs in deep learning do not exist in human-readable code form but exist as hundreds of thousands of parameters. Since they are just numbers, it is impossible for humans to read and interpret them. Given that a program has been developed that can correctly determine cat images with considerable accuracy, it is not possible to understand why the program makes such a judgment even by looking through neural networks.

Therefore, it is difficult to debug deep learning programs in the same way as conventional programming. It is difficult at first to identify the defective part, and even if you found out, there is no alternative but to adjust hundreds of thousands of parameters to correct it, so it is almost impossible for a human to touch directly. For this reason, it is customary to relearn after making adjustments such as increasing, re-assembling data, or modifying the design of the neural network.

Although it is possible to correct a program that has failed by relearning, it is also challenging to find out the cause itself. For example, think about an autonomous driving car using deep learning, which is currently actively researched and developed. Suppose that it turns out that an autonomous vehicle caused an accident and that the cause was “a failure in the determination of a deep learning program.” What can be a problem here is that we cannot investigate the cause any further. When something goes wrong, many people want to know the reason, but deep learning software cannot currently meet such social demands.

This problem is being actively studied in the machine learning community as a problem of “explainability” or “interpretability.” Some solutions may appear in the near future. However, nowadays, programs created by deep learning can only be treated basically as black boxes.

In the first place, even if it becomes possible to explain the behavior of such a program in the future, it is not clear whether humans can understand the explanations. As mentioned earlier, programs created by deep learning are inherently sophisticated enough to be unreadable to humans, and their “algorithm” may exceed the limit that humans can interpret. If we were able to translate deep learning programs into pseudo code, it could be hundreds of millions of lines, or too complex, that humans might not understand. This is equivalent to the problem of how human beings can interpret the meaning of the current highly developed Shogi software pointing to and moving the hand.

Interpretation of Deep Learning in Hoare Triple

Now that we have seen deep learning tasks for each of preconditions P, postconditions Q, and programs c, let’s summarize the discussion so far.

In deep learning, coding defines a space of the program. In other words, in the past, coding was to define one c that satisfies {P} c {Q}, but in deep learning, coding is to define a set of c that satisfies {P} c {Q}. Note, however, that in deep learning, the interpretation of Q has been replaced by statistical one. Since the current Hoare triples cannot handle such statistical Q, we will extend Hoare triples in the following; while a Hoare triple in conventional software development can only take two values, “satisfied” or “not satisfied,” in the following, we will think {P} c {Q} is satisfied at \(y\) for \(y\) that takes a real value between \([0, 1]\).

Based on the above, I will write [c] for the set of c and {P}[c]{Q} for a condition that all elements of [c] satisfy the given precondition P and postcondition Q, so the programming process in deep learning can be considered as follows.

- Intensionally define the tasks

PandQthat you want something to do with deep learning. - Design a program space

[c]that statistically satisfies{P}[c]{Q}. - Collect and build concrete examples (tests) that describe

PandQin an extensional manner. - Let a computer search for the optimal element

cof[c]that satisfies{P}c{Q}.

The 2. and 3. above are interchangeable or can be done in parallel.

In deep learning, it is up to the computer to pick one best program c from [c]. On the other hand, what humans focus on coding is how to define an efficient search space, and what kind of space can be designed to find a program that can be processed accurately and at high speed.

Programming in deep learning cannot be completed only by coding, and it is necessary to collect and build a large amount of test data and provide them to a computer. Because the amount of test data is so large, the challenge is how to provide it efficiently or how to reduce it fundamentally.

Summary and Outlook

This article introduced an attempt to position deep learning as a new programming paradigm within the framework of computer science. The term Software 2.0, which has come to be often found overseas, can be considered as one such attempt.

Lastly, I would like to conclude this article by introducing my vision from the perspective of computer science.

Attempts to capture deep learning from the perspective of computer science may be summarized as a phrase saying “we want program semantics of deep learning” as we go further. Program semantics is a question of “how is the program interpreted?” It is all the foundation that gives the program correctness. The background behind my intention to write this article is to clarify the current situation that the semantics of deep learning programs can only be defined very vaguely.

In fact, this article is a product obtained while trying variously to consider the axiomatic semantics of deep learning. Here, axiomatic semantics refers to the program semantics given using Hoare triples. When Hoare triples are used, as described in this article, the specification and program are treated as inextricable, the program is regarded as a black box, and we can define the semantics only by focusing on input/output (or before and after execution) and from the behavior observable from outside. Because of these characteristics, Hoare triple is considered to be a good match when thinking about deep learning. Thinking deep learning semantics in line with this axiomatic semantics may be the most realistic shortcut for capturing deep learning in computer science.

In conventional software development, the specifications P and Q in {P} c {Q} and the program c are inextricably linked. Even in deep learning, the specifications P and Q and the program c (or the space of the program [c]) should be inextricably linked. Further analysis of the relationship between P, Q, and c ([c]) in deep learning will give you a better understanding of what deep learning is in computer science.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Yusuke Endoh and Masahiro Sakai for helping to correct this sentence and giving valuable comments on the content.

Footnotes

-

If you are familiar with statically typed languages, this triple can be interpreted as “a function with type

P → Qisc” in this article. ↩ -

When dealing strictly with Hoare triple, it is necessary to consider the termination of the program

c. But in deep learning, which is the subject of this article, there seem no such situations where it gets stuck in an infinite loop. So I will not consider the termination here as well. ↩ -

For a problem where human recognition error rate is 5.1%, Microsoft Research achieved 4.9% in February 2015 and Google achieved 4.8% in March 2015. ↩

-

Goodfellow, I. J., Shlens, J., & Szegedy, C. (2014). Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6572 ↩

-

The pioneering research was DeepXlore [https://arxiv.org/abs/1705.06640], and several improvements have been proposed. ↩

-

Li, Z., Ma, X., Xu, C., & Cao, C. (2019). Structural Coverage Criteria for Neural Networks Could Be Misleading. In the 39th International Conference on Software Engineering: New Ideas and Emerging Results Track. Retrieved from http://moon.nju.edu.cn/people/xiaoxingma/pubs/2019-ICSENIER-ZLi-Misleading.pdf. ↩

Comments